REVIEW: The Building of So Many Stories

Caroline Sy Hau and Patricio N. Abinales

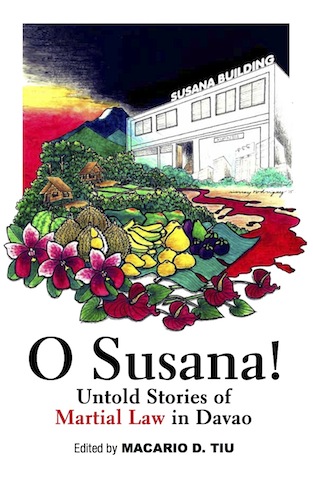

Review of O Susana! Untold Stories of Martial Law in Davao

Edited by Macario D. Tiu

Ateneo de Davao University Publication Office, 2016. 326 pp.

Between the early 1970s and the early 1980s, the two-storey, wood-and-concrete Susana Building along J.P. Laurel Avenue, Davao City, was instrumental in creating a community of “service providers” (to use Cesar Ledesma’s term) who spearheaded not only civic, religious, artistic, and development projects in Mindanao but also aboveground opposition to the Marcos dictatorship.

Edited by the eminent scholar, activist, and creative writer, Macario D. Tiu, O Susana! collects the stories of these denizens, who called themselves “Susanistas” and were active in the church, corporate, artistic, and civil society organizations that shared office space in this building.

While underground resistance to the Marcos dictatorship is well-known and -documented by academic studies and memoirs, aboveground activism especially by faith-based community organizers and cultural workers has received less attention.

On a given day, you saw Karl Gaspar exchanging gossip with Chito Ayala, or Nanay Soleng Duterte berating then Councilor “Nonoy” Garcia for not acting fast on her proposal to have bicycle lanes along the City’s main streets and asking Rey Teves and Jess Dureza what their plans were as student activists now that rumor had it that martial law might be declared any time.

Susana “alumni” also include Carlos “Sonny” Dominguez, Jr. of the Pilipino Banana Growers and Exporters Association; Alfredo “Freddy Salanga” of the Banana Export Industry Foundation; Paul Dominguez and Ernie Garilao of the Philippine Business for Social Progress; Orlando “Orly” Carvajal of the Mindanao-Sulu Secretariat for Social Action and the Mindanao-Sulu Pastoral Conference Secretariat; Inday Santiago of the Coordinating Council of Organizations of Davao; and Nelly Lanorias of Konsumo Davao, to name a few, who would go on to play important roles in the post-EDSA government and society.

What is remarkable is how comfortable these folks were with each other, despite their class, ethnic, political, and religious differences. O Susana! makes a compelling argument for the crucial role played by networks that cut across sectoral and ideological lines in connecting people to a common cause in the darkest hours of martial law.

But what makes O Susana! special is the vim and vigor with which the contributors, some of whom are taking up the pen for the first time, tell their own stories of fact-finding missions in heavily militarized zones, close collaboration with indigenous peoples and their communities, and promoting artistic endeavors through writing and theater workshops.

But what makes O Susana! special is the vim and vigor with which the contributors, some of whom are taking up the pen for the first time, tell their own stories of fact-finding missions in heavily militarized zones, close collaboration with indigenous peoples and their communities, and promoting artistic endeavors through writing and theater workshops.

Marilen Abesamis writes movingly of finding “Love and Laughter” amidst the “new normal” of “killings, grenades dropping at bus stations, skirmishes at public places, and clashes between the New People’s Army (NPA) and government forces in the countryside.” Joey Ayala makes his first album, Kaya nauna ang Panganay ng Umaga, in the DEMS recording studio. Wilfredo Rodriguez runs the training sessions that enable parishioners to put out their own newsletter.

Telling details abound. When Orly Carvajal, who helped establish the Christians for National Liberation, receives a “polite invitation” to the local military camp, he is informed by the Commanding General that the suggestion to subject him to “tactical interrogation” comes from his “fellow man of the cloth.” Cesar Ledesma recalls a conversation with a “courteous, soft spoken” military officer who is negotiating the surrender of a leading Muslim rebel, only to learn the next day that the officer has been killed in an ambush.

O Susana! is a memorial to the living and the dead. Karl Gaspar, himself detained for 22 months, pays homage to Amasona like Sisters Regina Pil and Christine Tan who are not afraid to speak up and help the families of “the disappeared, imprisoned, tortured and ‘salvaged’.” Jeanette Birondo-Goddard and Avelina Baliong-Engen honor the memory of Buyog (Manuel Ando), who connects the Citizens Council for Justice and Peace to the datus of Paquibato District to avert a pangayaw aimed at avenging the intrusion into the Ata ancestral domain and the kidnappings and killings of Ata Manobo by armed groups allegedly employed by a Marcos crony.

These heartfelt accounts have only increased in poignancy and urgency since the volume’s publication five years agobecause, as some of the contributors have rightly pointed out, many Filipinos have either forgotten or do not know what life had been like under the Marcos regime. “But,” in the words of Tranquilino Cabarrubias (translated by Alberto Cacayan): “my heart is certain about one thing/In a surging burst of pure courage/You shall carry on till freedom is attained.”

And what are we to make of the following account by Leon Bolcan, a former MISSSA staff member and member of the leftwing National Alliance, following his arrest and torture for the third time:

Alas 2:00 sa hapon, miabot si Vice-Mayor [Rodrigo] Duterte sakay sa iyang Willys nga sakyanan. Ug tuod man, nakagawas mi dala ang among mga bag ug bakpak lulan sa iyang sakyanan. Iya ming gidala sa Sangguniang Panglunsod. Naa didtoy taga media nga mo-cover unta sa maong panghitabo apan iya kining gipugngan. Gipasulod mi niya sa iyang opisina ug gilektyuran. “Mga gahi kamog ulo. Kusog ang bagyo. Pasilong una mo kay kusog ang ulan. Mabasa gyod mo.” Mora mig mga manok nga nabasa sa ulan nga nagpasalamat kang Vice-Mayor Duterte. Paggawas namo sa iyang opisina, nangadto dayon mi sa opisina sa Task Force Detainees (TFD) sa Juna Subdivision, Matina, Davao City aron ireport ang among kaso.

It was no secret to many in Davao that Duterte had a good relationship with the Left as well as other anti-Marcos groups. This facet of Duterte’s character has been given only perfunctory attention by scholars, policy analysts, and public intellectuals in their accounts of his presidency. We suspect that this oversight may be due to the fact that there has been little data to work with. It does not help that many in the Duterte Studies Industry do not speak either Visayan or Davao Tagalog, nor have they spent an extended time or two in Davao.

Bolcan’s story is revealing as it is the first time that this “bromance” (in today’s millennial lingo) is on full display. Surely this was not the only case. It certainly complicates the picture of Duterte as strongman.

Finally, O Susana shows that there is more than meets the eye when we look more closely at Davao City life, society, and politics in the 1970s and 1980s. Ateneo de Davao University Press has a Facebook account devoted to the book launching in 2016. As you listen to the authors– older, grayer, wiser – you cannot help realizing even today that the “thing” that makes Davao City unique and storied as a political arena is still very much there. Those interested in studying Duterte will find in this book some answers to the question of why we live such baleful lives under the sixteenth president of the Philippines.

(Caroline Sy Hau and Patricio N. Abinales are faculty members at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University, and the Department of Asian Studies, University of Hawaii-Manoa, respectively. Abinales is from Ozamiz City)

REVIEW: The Building of So Many Stories

Source: Viral News Filipino

0 Comments